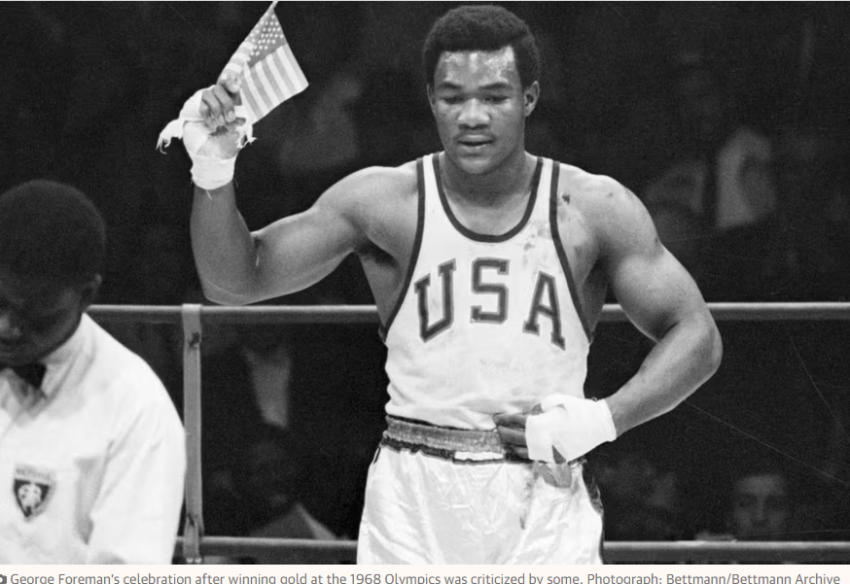

When George Foreman, a teen from Texas, won gold at the 1968 Olympics and waved a tiny American flag in the boxing ring, he had little awareness of the political minefield below his size 15 feet. The moment, captured by television cameras for an audience of millions during one of the most volatile periods in American history, was instantly contrasted with another image from two days earlier at the same Mexico City Games: Tommie Smith and John Carlos, heads bowed. Black-gloved fists raised in salute during the US national anthem, a silent act of protest that would become one of the defining visuals of the 20th century. Their message was clear: an attack on the nation that sent them to compete while continuing to deny people of color their civil rights. Their action was seen as defiant resistance, and Foreman’s as deference to the systems of oppression they were protesting.

But that reading, while emotionally understandable amid the fevered upheaval of 1968, misses something deeper – about Foreman, about patriotism, and the burden of symbolic politics laid on the shoulders of Black athletes.

To understand the backlash the 19-year-old Foreman faced in the context of 1968, particularly from within the Black community, is to understand the mood of that year: a procession of funerals and fires, of uprisings in Detroit and Newark, of young people trading dreams of integration for the sharp rhetoric of militant self-determination. Dr Martin Luther King Jr had been gunned down in Memphis just months earlier. Black Power was no longer a whisper in back rooms or college classrooms – it had become a rallying cry, a style, a stance. And in that charged atmosphere, there seemed to be only one acceptable way to be Black and politically conscious: with fist raised, spine straight, voice sharpened by injustice.

In that climate, Smith and Carlos’s silent, defiant protest was seismic. They paid dearly for it – expelled from the Games, vilified at home, and exiled from professional opportunity for years. They were heroes, then and now. But the demand for unity behind that particular kind of protest was strong. To many, in that moment, there was only one acceptable way to be Black and political. Foreman’s flag violated that code. It did not speak the language of protest. It didn’t say who the enemy was. And so, some saw it as a profound misstep.

Foreman had long insisted that there was no statement embedded in the flag he waved. “I didn’t know anything about [the protest] until I got back to the Olympic Village,” he said years later. “I didn’t wave the flag to say something,” I said. Because I was happy, I waved it. That kind of apolitical happiness wasn’t just seen as suspicious – it was infuriating to those risking everything to challenge the systemic racism at the foundation of American society. The fact that the mainstream white media embraced Foreman as a “good” Black athlete in contrast to Smith and Carlos only deepened the rift. He was positioned, perhaps unintentionally, as the safe symbol of patriotism, the counter-image to fists in the air.

But Foreman’s tale was never straightforward. He grew up poor in Houston’s Fifth Ward, a tough and segregated neighborhood. He discovered boxing through the federal anti-poverty program Job Corps. For Foreman, the flag represented a nation that had provided him with a means of escape rather than a government that had failed him. His patriotism was anything but performative; it was deeply personal.

Too frequently, diverse Blackness experiences are mistaken for ideological betrayal. In America, not every act of pride is an admission of the country’s sins. Sometimes it’s a hard-earned survival mechanism. For Foreman, the flag may have symbolized escape, opportunity, and the dream that somehow, despite it all, he belonged.

Still, the criticism followed him, stubborn and sharp. He was branded an Uncle Tom, accused of pandering to white America and made to feel, by his own account, unwelcome in many Black spaces. His response was not to explain but to retreat. In the ring, he became a fearsome presence – angry, sullen, and distant. Outside it, he said little and seemed to carry a quiet fury beneath the surface. When he laid waste, Joe Frazier, in 1973, knocking him down six times in two rounds to claim the heavyweight crown, he celebrated not with a grin but with a kind of grim inevitability. He looked less like a champion than an avenger.

However, narratives tend to change, particularly in American life, and Foreman’s ended up changing. Not long after losing it all with his crushing loss to Muhammad Ali in Zaire the following year – a defeat that humbled and haunted him – he disappeared for a decade. He became a preacher, discovered God, and established a youth center. When he returned to boxing in the late 1980s, older, heavier, and unfashionably gentle, the public met him with something approaching affection. Now he smiled. He cracked jokes. He appeared on talk shows. In addition, it did not feel like he had been redeemed when he regained the heavyweight title at the age of 45 in one of the sport’s most unlikely comebacks; rather, it felt more like he had been reinvented. Millions of countertop grills bearing his name were being sold by the same man who once waved the flag and was derided for doing so. He starred in a primetime network TV sitcom. He named all five of his sons George. He leaned into the myth and made it charming. In doing so, he reshaped the cultural meaning of his image – from the quiet bruiser to the joyful elder statesman, a symbol of resilience, reinvention, and a kind of pragmatic hope. There’s a credible argument that he succeeded Bill Cosby as America’s dad.

The radical clarity of Smith and Carlos’s gesture should not be lost on us. We shouldn’t also mistake Foreman’s action for something else. However, maybe we can now accommodate both. Black patriotism has always contained tension, ambiguity, and contradiction. It has never been a monolith. Some express it through protest, others through perseverance. A fist raised, a flag waved – both can be acts of love, not of submission, but of insistence: that the country be made to live up to its promise. And in a nation that often demands that Black people perform either rage or gratitude, George Foreman dared to be something else: complex.

The enduring lesson of 1968 is not that one form of Black political expression is inherently more valid than another, but that the burden placed on Black athletes to symbolize a collective experience is often impossibly heavy. Every move is looked at carefully. Every silence is interpreted. Every celebration is suspect. In this way, Foreman’s flag was never just about joy; it was also about how impossible it was to be apolitical in a body that was already politicized by history. He did not salute a perfect America. He saluted the possibility of one.